– With Additional Considerations for Patients Undergoing General Anaesthesia for Surgery

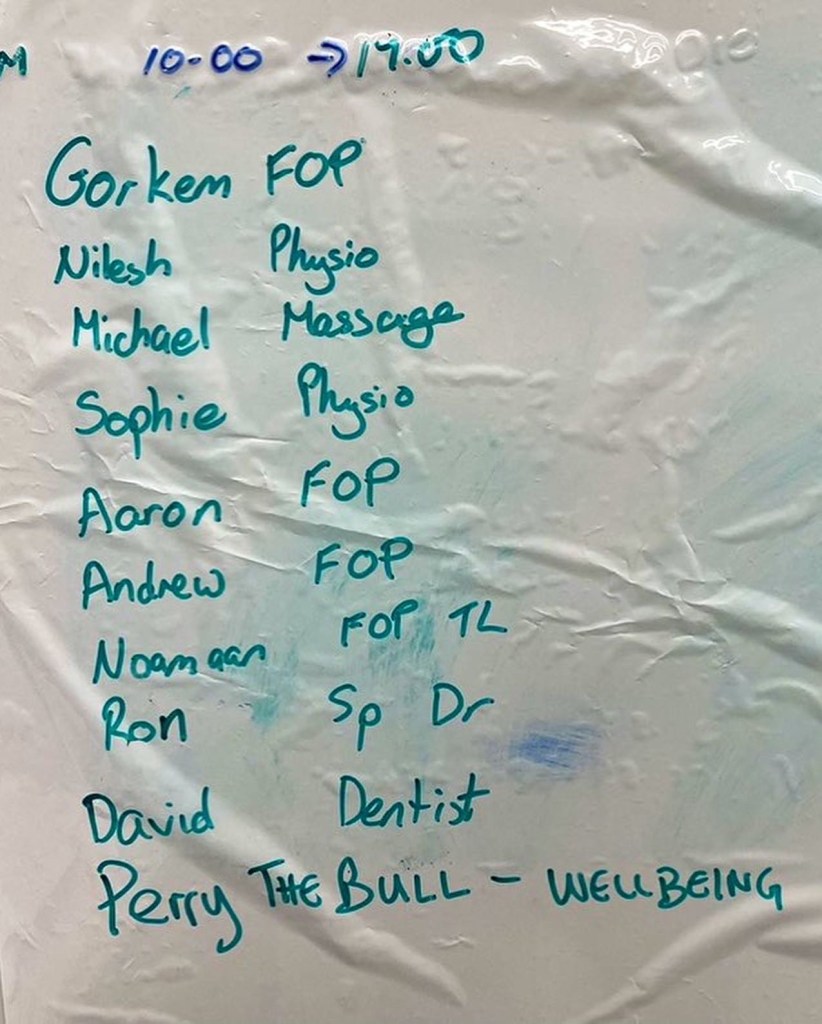

Noamaan Wilson-Baig

Paper Reviewed – Nakagaito, M., et al. “Impact of SGLT2 Inhibitor Withdrawal on Heart Failure Outcomes.” Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024 May 29;13(11):3196. doi: 10.3390/jcm13113196 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11172815/

Objective:

This study assessed the effects of discontinuing sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) on hospitalization rates and medical costs in heart failure (HF) patients.

Key Findings:

Hospitalization Rates:

Patients who discontinued SGLT2i had higher all-cause hospitalization rates compared to those who continued therapy (74.5% vs. 57.8%).

The withdrawal was independently associated with increased hospitalizations (hazard ratio 1.41, p < 0.05).

Heart failure-related readmissions were significantly higher in the withdrawal group (21.6% vs. 7.5%, p = 0.007).

Medical Costs:

Despite differences in hospitalization rates, the two groups had no significant difference in total medical costs.

The withdrawal group had higher costs for HF-related hospitalizations, while the continuation group had higher costs for cardiovascular disease-related hospitalizations.

Clinical Implications:

SGLT2i withdrawal may lead to increased hospitalizations, particularly for HF and non-cardiovascular conditions, without reducing overall medical costs.

The pleiotropic effects of SGLT2i, including its anti-inflammatory and renal protective properties, may reduce these adverse outcomes.

Study Design:

– This was a single-centre, retrospective observational study involving 212 HF patients who initiated SGLT2i during hospitalization.

– Patients were followed for a median of 695 days.

– The primary outcome was all-cause hospitalization, and secondary outcomes included HF-specific hospitalizations and medical costs.

Limitations:

Non-randomized Design: Selection bias and confounding factors may have influenced outcomes.

Single-Center Study: Results may not be generalizable to all populations.

Heterogeneity of SGLT2i Used: Different drugs within the class may have varying effects.

Conclusions:

The study concluded that continued SGLT2i therapy reduces hospitalization events in HF patients without increasing medical costs. Discontinuation of SGLT2i is associated with higher HF-related and non-cardiovascular hospitalizations, highlighting the need for cautious evaluation before withdrawal.

Reference:

Nakagaito, M., et al. “Impact of SGLT2 Inhibitor Withdrawal on Heart Failure Outcomes.” Journal of Clinical Medicine. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11172815/.

Critical Analysis of this Study

Strengths

- Relevance to Clinical Practice:

- The study investigates a critical gap in HF management: the consequences of withdrawing SGLT2 inhibitors, a commonly prescribed drug class with proven benefits in HF management.

- Its focus on real-world data provides insights beyond controlled randomized trials.

- Robust Outcomes:

- The study evaluates clinically meaningful outcomes, such as all-cause hospitalizations, HF-related readmissions, and medical costs.

- The extended follow-up period (median 695 days) strengthens its conclusions on the chronic impact of withdrawal.

- Comprehensive Data Collection:

- The authors considered multiple confounding factors, including NYHA class, eGFR, and HF medication regimens, included in multivariable analyses.

- Including non-cardiovascular hospitalizations provides a holistic view of the impacts of SGLT2i withdrawal.

Limitations

- Observational Design:

- The non-randomized, single-centre design introduces selection bias and limits causal inference.

- Withdrawal group patients were older and had worse baseline conditions (e.g., higher BNP levels), making direct comparisons with the continuation group less robust.

- Sample Size and Generalizability:

- The sample size (n=212) is modest, especially for subgroup analyses.

- The single-centre study in Japan limits generalizability to broader populations with different healthcare systems or practices.

- Uncontrolled Confounders:

- Patients in the withdrawal group had higher NYHA class III/IV symptoms and more comorbidities, potentially driving higher hospitalization rates independently of SGLT2i discontinuation.

- Other HF therapies were adjusted during follow-up, which could confound the observed effects.

- Economic Analysis:

- The medical cost analysis is limited by significant heterogeneity in hospitalization events and treatments.

- The cost findings may not apply to other healthcare systems with different pricing and reimbursement structures.

- Limited Exploration of Causal Mechanisms:

- While the study mentions the pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors, it does not delve into the specific physiological reasons for the observed increase in non-cardiovascular hospitalizations post-withdrawal.

- Limited Categorisation of Patients Who Stopped SGL2:

- The study does not explicitly categorize or isolate those who stopped SGLT2i exclusively due to critical illness. The reasons for withdrawal are listed collectively (e.g., urinary tract infections, fasting, etc.), suggesting that some patients in the withdrawal group may have stopped the therapy for reasons unrelated to acute critical illness. This lack of specific categorization is a limitation when interpreting the study’s findings regarding critical illness as a direct cause of SGLT2i withdrawal.

Interpretation of Results

The study confirms that discontinuation of SGLT2 inhibitors in HF patients is associated with worse outcomes, specifically increased hospitalization rates. However, the findings must be interpreted cautiously due to the observational nature and inherent biases.

The lack of significant differences in total medical costs between groups is intriguing. It suggests that while HF readmissions increase with SGLT2i withdrawal, these costs may be offset by fewer high-cost cardiovascular interventions (e.g., device implants) in the withdrawal group, possibly reflecting poorer candidates for such therapies.

Bottom Line

This study provides valuable real-world evidence that discontinuing SGLT2 inhibitors in HF patients can lead to worse clinical outcomes, notably higher HF-related and non-cardiovascular hospitalizations, without reducing overall healthcare costs. While it highlights the risks of abrupt withdrawal, its observational design and confounders limit causal inference. Future randomized controlled trials or more extensive multicenter studies must confirm these findings and provide evidence-based guidelines on managing SGLT2i therapy during acute or critical illness.

Takeaway: Whenever feasible, the continuation of SGLT2 inhibitors should be prioritized in HF management, and withdrawal should be carefully evaluated on a case-by-case basis, considering the potential risks of increased morbidity.

Key Considerations for patients on SGL2 having general anaesthesia for surgery

- Risks of SGLT2i During Perioperative Period:

- Euglycemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis (euDKA): SGLT2i increases the risk of euDKA, especially during periods of fasting, reduced caloric intake, or physiological stress, which are common in the perioperative setting. This is a significant concern for patients undergoing surgery.

- Volume Depletion: SGLT2i promotes osmotic diuresis, leading to dehydration and haemodynamic instability, especially if fluid intake is restricted before surgery.

- Benefits of Continuing SGLT2i:

- SGLT2i have significant cardiovascular and renal protective effects, particularly in heart failure (HF) patients. Abrupt withdrawal may increase the risk of HF exacerbations and hospitalizations, as evidenced in the study.

- Although this has not been specifically studied, their anti-inflammatory and oxidative stress-reducing properties could theoretically provide perioperative benefits.

- Anything this study provides for Anaesthetists?:

- The study indicates that discontinuation of SGLT2i is associated with increased all-cause and HF-specific hospitalizations. However, the study did not specifically evaluate patients undergoing surgery or assess outcomes related to perioperative SGLT2i use.

- Withdrawal during hospitalization, particularly in acutely ill patients, was linked to worse outcomes. This suggests caution when stopping SGLT2i, even during physiological stress like surgery.

Clinical Guidelines, Recommendations and Further Research

Most current guidelines recommend temporarily discontinuing SGLT2i in the perioperative period to mitigate the risk of euDKA and volume depletion. Specifically:

- Timing: SGLT2i are typically stopped 2-3 days before surgery (or 4 days for ertugliflozin due to its longer half-life) and resumed once the patient is hemodynamically stable and can resume oral intake.

- Monitoring: Blood glucose and ketone levels should be closely monitored during the perioperative period, particularly for signs of ketoacidosis.

These recommendations are aligned with safety practices to minimize serious metabolic complications associated with SGLT2i use during surgery.

Further research

Further research is essential to better understand the short-term and long-term effects of discontinuing SGLT2 inhibitors in the perioperative period. While existing evidence highlights the benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure management, their withdrawal during surgery—often due to concerns about euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis or haemodynamic instability—remains an underexplored area. Studies are needed to assess the impact of discontinuation on perioperative cardiovascular outcomes, including heart failure exacerbations, arrhythmias, and mortality, as well as metabolic complications. Such research would provide critical insights to guide evidence-based recommendations for the safe and effective perioperative management of patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors.

Conclusion

While the study highlights the risks of SGLT2i discontinuation in HF patients, the perioperative context involves unique risks such as euDKA, dehydration, and haemodynamic instability, which justify the temporary withdrawal of these medications. Patients should generally stop taking SGLT2i before surgery, requiring general anaesthesia, but with careful monitoring and prompt resumption once it is safe. The decision should always be individualized, weighing the risks of continuation (euDKA and volume depletion) against the potential for HF exacerbation, particularly in high-risk patients.

Disclaimer

The content of this document reflects the personal views, considerations, and thoughts of the author, a practising critical care doctor and anaesthetist. The information provided is intended for informational purposes only and should not be interpreted as professional advice or formal guidance.

This document has not been peer-reviewed, and its content should not be used as a substitute for established clinical guidelines or expert consultation. Readers are advised to exercise their own professional judgement and consult relevant evidence-based resources or guidelines when making clinical decisions. The author does not accept liability for any consequences arising from using the information presented in this document.